A Man of Substance

When Fernando Casasempere moved from Chile to London, in 2007, the first exhibition he saw was Sensation, the famous (and infamous) showcase for the Young British Artists at the Royal Academy. “It made me feel prehistoric,” he says. And little wonder. He’d come from an artistic culture still rooted in modernism, and had an personal aesthetic orientation toward Mesoamerican culture. After studying sculpture in Barcelona and then returning to Santiago, he’d found immediate success, securing major museum exhibitions despite his youth. He felt at once confirmed and confined; it was almost too easy. Casasempere knew that to grow as an artist, he would need to seek out new challenges – and so it was that he came to London, and found himself face-to-face with a shark floating in formaldehyde.

All these years later, he’s still working out the implications of that transition – and working, and working. His foundation is still back in Latin America: its sublime landscapes, its characteristic materials and colors, and above all, the powerful imprint left by its ancient civilizations. He cannot help but wonder what those cultures would have become, had they not been devastated by colonization. It’s impossible to know, but – though Casasempere is not himself of indigenous heritage – his work gives us the poetic space in which to consider the question. At the same time, he has spent nearly three decades observing the London art scene, imbibing its cosmopolitan energies, grappling with its self-conscious avant-gardism, noticing its blind spots (including the one that, until recently, has kept ceramics hidden from view).

It has been an extremely complex situation in which to make art. But it’s of complexity that discovery comes, and as they say, the only way out is through. And so Casasempere hurls himself headlong into the studio every day, knowing that the only solution to deep contradiction is equally profound creativity. His output is titanic. Some of his installation works have been comprised of thousands of elements. Others are nature mortes laboriously carved – liberated, one might say – from solid masses of clay. Not a few verge on the monumentality of architecture. Everything bears the mark of his own strong hands. He generates layer after layer of meaning, all of it is grounded in his touch.

And grounded is the word, here. His surfaces conjure the austere, otherworldly grandeur of Chile, the dry cracked salt flats of the Atacama Desert, the blasted remains of potassium mines, eroded formations of white marble. Like those amazing natural landscapes, Casasempere contains multitudes: to visit his studio is to survey the possible modes of working in clay. A series of recent “paintings” in clay could be satellite images of that terrain, or alternatively, magnifications of just a few inches of ground. (Like any form of abstraction, they have no single scale.) He does make vessels, the anchoring typology of the discipline – most recently, imposing black pieces that call to mind draped figures standing in contrapposto, their silhouettes delicately puckered inward here and there to create an unforgettably particular presence.

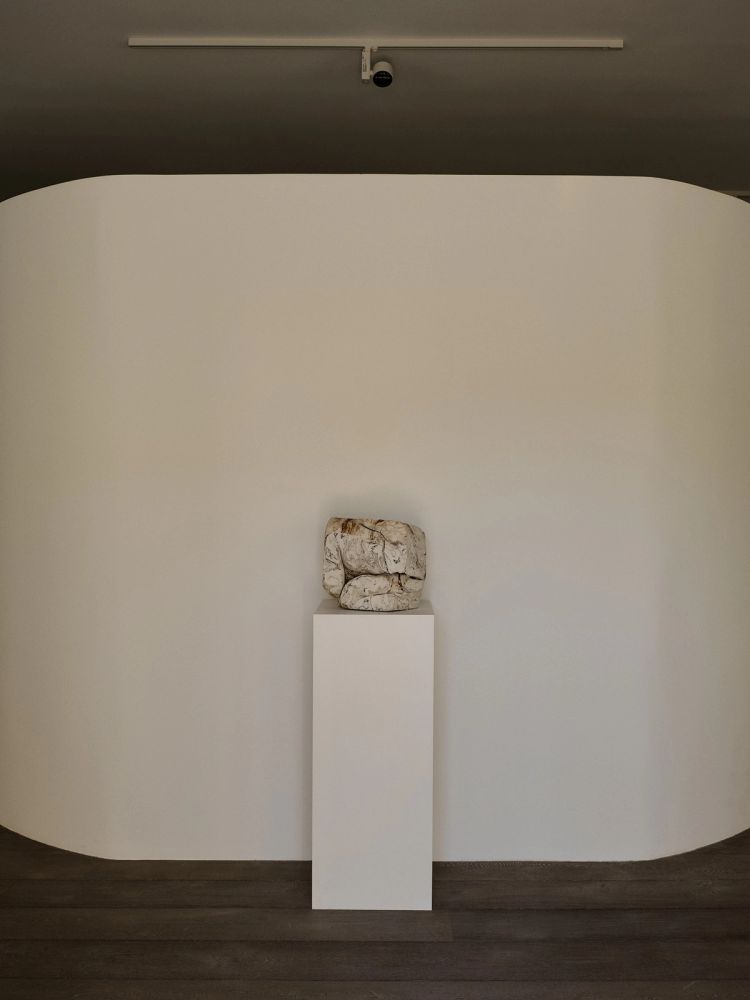

His affinity for geology comes across in pebble-like forms, while his love of ruins is expressed in architectonic sculptures built from tumbling blocks. Both these bodies of work are composed of aggregated clays, mixtures of what were already mixtures, building on his years of experimental recycling. Passages in porcelain and swirls of blue cobalt lend brightness, the palette of refined Chinese ceramics transmuted into something raw and archaic, as if he were reaching back through the canon to find its source.

Paradoxically, it is that impulse toward first principles that makes Casasempere such a vital force in contemporary art. He doesn’t just show things to us – what it means for a civilization to be destroyed in its prime; what it is for nature itself to be convulsed – he gives us a way to feel them. This imbues his work with a very specific, very intense kind of urgency. Has he accommodated himself to the dynamics of his adopted home, the attitudes of an art scene that is itself shark-like, restlessly moving on to the next thing? Not at all. His practice is too seismic for that, too animated by deep currents to ever be superficially fashionable. Here’s a prediction, though: in fifty years, or five hundred, when historians look back at our moment, Casasempere will loom large. For he is making art for the ages; and that is the only way to speak truly to the now.

Words

- Glenn Adamson

Photos

- Rich Stapleton